Although I’m not always sure of the motivations, there is a

politics to the reporting of music industry sectors. In particular, there has

been a desire to emphasise the health of the live music industry at the expense

of recorded music.

The statistics that have been

most widely used in support of this scenario come from Adding Up the Music Industry, a

series of reports issued by PRS for Music. Sadly these reports are no longer

compiled: the last of them concerns revenues for 2011. It calculates the total

money generated by the UK music industry in this year at £3,793m. Out of this

figure £1,057 comes from business-to-business income and £2,736m from

business-to-consumer. The latter is divided into £1,112m for recorded music and

£1,624m for live music.

And so live music triumphs over

all other comers. It is this outcome that many analysts have taken up and run

with. The reports have their problems, however. Live income is compiled in a

different manner to the other streams. As well as documenting the primary

market – the money spent on purchasing tickets from ticket agents and venues –

the figure includes secondary ticketing and ancillary spend. Secondary

ticketing is money derived from the resale of tickets. Although the report

states that this business model is ‘legitimate under UK law and is an

established practice’ it is somewhat contentious. Moreover, none of the money

from these sales goes to writers, musicians, publishers or record companies. At

the very least this income is comparable to the second hand sale of records, an

income stream that is omitted from the figure for recorded music. Under a different

legal system it could be considered more akin to bootlegging. The report

calculates its worth at £208m.

Ancillary spend is the extra

money that is spent at gigs and festivals: the purchase of ‘merchandise, food,

beverages, parking and public transport’. It is questionable whether the money

spent on food, drink and transport should be included as part of music industry

income. Some money from these sales might trickle through to a few performing

artists, but it will be tangential and minimal, and in these instances should

be included in the business-to-business figures, rather than

business-to-consumer. Moreover, although these sales are included in the live

income stream, money spent on food, drink and parking when going record

shopping is not included in recorded music. This is the case even when the

record shops are serving food and drink themselves.

Artists can make money from merchandise. There

are famous cases where bands have made more money from t-shirt sales than they

have from ticket sales. It is unfair, however, to include the sales of

merchandise in the live tally while omitting it from recorded music: these

reports do not include the sale of t-shirts and

other merchandise in record shops.

It is difficult to calculate how

much ancillary spend is worth as the 2011 report fails to provide precise

figures. The best it offers is that festivals and arenas each account for

‘around 25 percent of the market’ and that ancillary spend at festivals is

equal to ’95 percent of the average face value ticket per person’ while the

‘level for most other venue sizes was between 35 and 50 percent’. At the very

least, then, ancillary spend is equivalent to a third of the money spent on

primary tickets. The live income stream can therefore be broken down into £208m

for secondary ticket sales, £472m for ancillary spend and £944m for primary

ticket sales. It is only the latter figure that can effectively be compared

with the statistics for recorded music. Looked at this way, live income is the

lower of the two.

Recorded music is unfairly

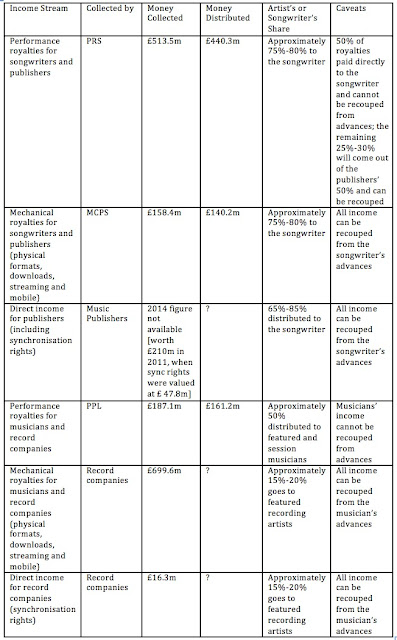

represented in other ways. In 2011 PRS for Music reported £65m income for

‘mechanical revenues’, i.e. the money that songwriters and publishers earn from

record sales. Adding up the Music

Industry contrasts the

‘continued decline of the recorded music market’ with the ‘phenomenal revenues’

earned in the live sector. However, live income for PRS for Music was £23m,

which is lower than the mechanical income derived from its MCPS alliance.

In addition, the summarising

table in the report equates ‘recorded music’ solely with business-to-consumer

income. The total of £1,112m is made up of ‘payments for physical music

products, downloads-to-own and subscriptions’. This obfuscates the fact that

there is plenty of recorded music income that is derived business-to-business.

A substantial amount of the £448m that is attributed here to PRS for Music

comes from the use of recordings. Away from the main breakdown of figures, the

report itself allocates £101.6m of PRS income to ‘recorded music’. Sound

recordings also contribute to its other income streams: broadcast & online,

public performance, and international. It should be conceded that live music

also contributes to each of these remaining areas of business-to-business

income, albeit that it is recorded music that dominates when it comes to the

income generated by radio, television, the internet and the use of music in

public premises.

Moreover, while PRS for Music

owns the performance right in its members’ works, MCPS does not have complete

jurisdiction over the mechanical right. Its members can opt to self-licence the

use of recorded music for films, adverts and some television programmes. As

such, recorded music makes up a significant proportion of the music publishers’

direct income. Out of the £210m that is allocated to them in this report, £48m

comes from these sync rights. Ultimately, the mechanical income for songwriters

and publishers is holding up better than much industry reporting would lead us

to believe.

There is, in addition, plenty of

business-to-business income that makes its way to record companies and

recording artists. Recorded music is responsible for all of the £80m income that is

attributed to PPL and the £220m accorded to ‘record label direct revenues’. The

latter figure, in fact, includes some PPL revenue, as it is made up of ‘music

synchronisation, “360 degree” artist deals, concerts, music-related TV

production, broadcasting and public performance’.

Because of the way the figures

are reported, it is impossible to make an accurate tally for the income derived

from sound recordings. Recorded music is, however, worth considerably more than

the £1,112m highlighted in Adding up the Music

Industry. For the vast

majority of professional songwriters and musicians it provides more money than

live music does. While the same is obviously true for record companies, it

applies to music publishers as well.

There are good reasons why some

academics have seized upon PRS’s analysis: they like to emphasise the freedoms

of the live music scene in comparison with the tyranny of being signed to a

record company. PRS also has a performance emphasis. It is, after all, the

‘performing right’ that is enshrined in the society’s initials. Unlike the Musicians’ Union,

however, it does not campaign to keep music live: it collects money from the

performance of records as much as it does from performance in person. The

reasons why PRS have chosen to under-represent recorded music in their reports

are therefore obscure. Finally, I should concede that I have my own biases.

Although I do think I’ve provided a fairer way of reading the statistics, I

also know that I’m a record man. My main pleasures in popular music have always

come from recordings.