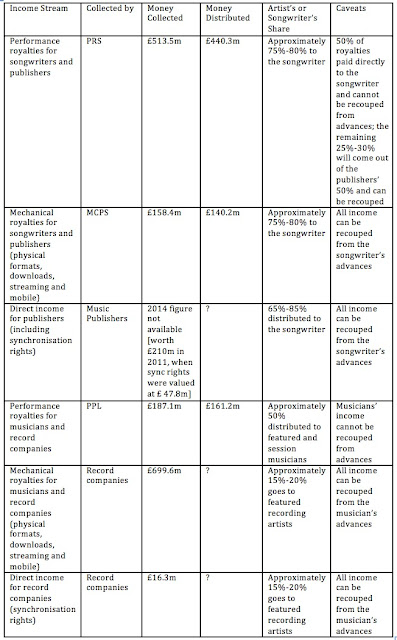

Following on from the previous two blog entries, which took

a comparative look at UK collection societies and the income earned by live and recorded music, I’ve made a stab at presenting UK recording and publishing

income for 2014.

The

statistics come from a variety of sources and it is risky to contrast them in

this manner. In addition, I don’t have privileged access to information. What

the figures should help indicate, however, is the relative health of each area.

I’ve also made a stab at indicating what proportion of money will go to the songwriter

or performing artist albeit that, unless the money is paid to them directly by a collection society, there are plenty of deductions and reductions that can be

added to the percentages given in the final column. Significantly and

spitefully, I have left out the money from live music, other than performance

royalties that PRS collects for songwriters and publishers.

While the collection societies and the British record

industries’ trade body BPI are reasonably good at indicating the money that has

come into the UK, they are less forthcoming about the money that is leaving. The

PRS, MCPS and PPL figures include income that is derived via reciprocal links

with foreign collection societies, but they fail to state how much is

going in the opposite direction. We don’t know how much money is going to

foreign songwriters, publishers, record companies and musicians. Moreover, the

record company figures also say nothing about the nationality of the musicians who

will be receiving the royalties, nor do they mention the record companies’

countries of origin.

According

to Will Page, there was a time when publishers’ income was divided 40:40:20

between performing, mechanical and synchronisation streams. The figures above

would indicate that the split is now divided something like 70:22:8. While this new division

highlights the decline of record sales, it distorts the income that can be made

from sync rights, which in overall terms has risen considerably in the past few

years. In fact, the £47.8m figure given in relation to songwriting sync rights

seems like a conservative reckoning, as does the £16.3m for sound recording

sync rights. The latter figure comes from IFPI, but in 2011 BPI were

regarding this income as nearer to £22m.

While the mechanical royalties

for songwriters and publishers are certainly declining, these figures show

them to be in better health than some PRS for Music information would have us

believe. The PRS for Music Financial Review for 2014 lists recorded music as

being worth £63.1m. The higher figure of £140.2m quoted here comes from MCPS’s

own Report and Statements and includes the mechanical income that is

derived from online licensing and broadcasting income.

PRS and

MCPS generally operate joint licences when it comes to online income (there are

also a few minor income streams that are jointly licenced between PRS and PPL).

There are no figures available to show how this income is split: PRS for Music instead publish a total figure of £79.7m. This figure is around 22% of the £363.8m that

record companies derive from downloads (£249m) and streaming (£115m). The

proportion of this money that makes its way to performing artists is much

debated.

But how much money in royalties is going to songwriters and artists overall?

A final, admittedly rough, outcome would reveal something like the following:

- Performance royalties for songwriters: £374m (roughly two-thirds of which is non-recoupable)

- Mechanical royalties for songwriters: £119m (recoupable)

- Sync rights for songwriters: £33m (recoupable)

- Performance royalties for musicians: £81m (non-recoupable)

- Mechanical royalties for musicians: £122m (recoupable)

- Sync rights for musicians: £3m (recoupable)

The money’s in the publishing; it is also in performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment